Pitt Rivers Museum

The Pitt Rivers is different to every museum I have ever been to. First things first- you have to go through another museum to get there. That's beautiful to start with, a journey through the Oxford Museum of Natural History is a great thing in itself and a stone archway opens out onto a tall (3 or 4 normal stories high) squarish room which is just packed with cabinets and cases and exhibits.

The Pitt Rivers is different to every museum I have ever been to. First things first- you have to go through another museum to get there. That's beautiful to start with, a journey through the Oxford Museum of Natural History is a great thing in itself and a stone archway opens out onto a tall (3 or 4 normal stories high) squarish room which is just packed with cabinets and cases and exhibits.

When the Lieutenant-General, Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers gave his collection to the University (c1884) he specified that the museum should be organised by typology rather than the usual topographical or chronological systems museum visitors and curators are used too. This important distinction is what gives the Pitt Rivers it's character and feel.

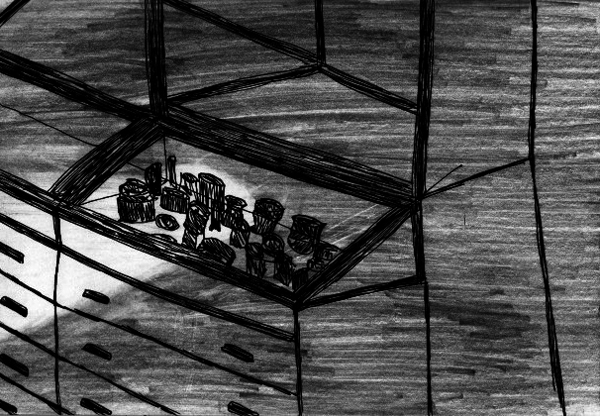

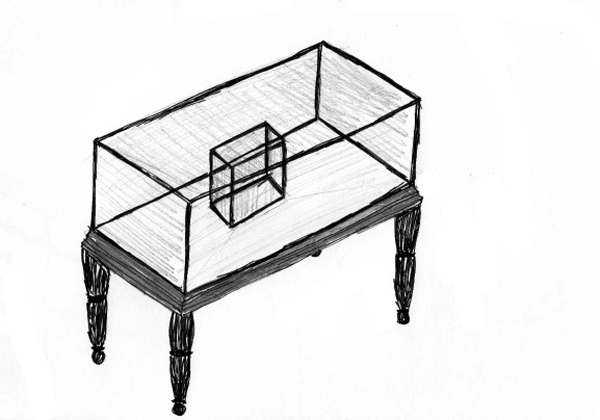

Another fantastic thing about the museum is that a lot of the objects are on show, rather than hidden in an archive. As Pitt Rivers said "It is better to show three objects rather than one". You can see everything. As this is the case the cabinets and display cases become very crowded- this is again to do with the typological organisation of the exhibits. Because many of the objects are delicate the light is low and visitors have trouble seeing objects placed at the back of cabinets, or underneath shelves. However visitors are encouraged to carry torches (available for loan at the gift shop), to be used to hunt down and observe the reluctant, hiding objects.

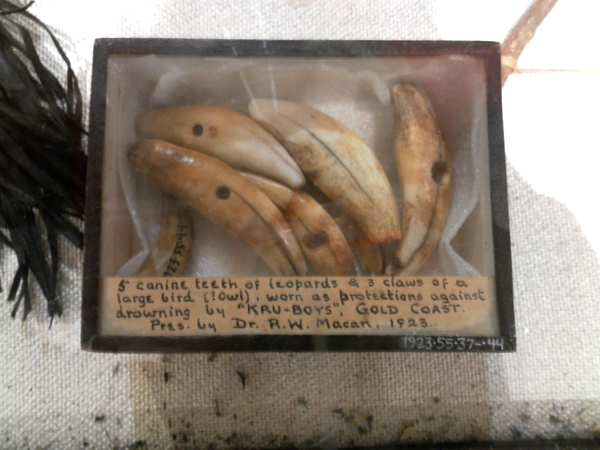

Every space is filled with exhibits, the cabinets stand proudly in the middle of the room, underneath and around these are drawers which are all searchable by the visitors. On the walls more cases and drawers below and cupboards and cases above reaching up to the ceiling out of reach and almost out of sight. Some of the cabinets even have other cabinets inside them. All of these objects are made from dark worn wood, giving a very comfortable and academic feel, and opening a drawer and discovering a cryptic exhibit is thrilling. The objects in the displays have handwritten labels, often on the actual objects themselves. This unusual cataloguing system seems to say that the objects themselves are not that precious and that it is more important that they are here among everything else, as if what they represent rather than the object itself is the focus of the museum. Very pragmatic.

Whilst Pitt Rivers did do some collecting first hand, most of his acquisitions came through other people: anthropologist, ethnographers, archeologist, soldiers, auction houses and friends. Of course the museum came about through his passion, interest and not least, wealth, but I like the idea that he became a hub of collecting so that people would have him in mind when they saw something they might think it suitable for his collection. People coming to him with offers rather than him hunting them down. Another interesting point to make on this topic is that only 7% of the current collection is made from Pitt Rivers initial donation. That means that thousands of exhibits have made there way to the museum since then, It links nicely to a theory I have about how a collection will often act as a sort of magnet for other similar items.

In terms of the specific objects I enjoyed included the famous shrunken heads, the swords (I am boy after all), the human heart in lead 'heart' shaped container and the Greenland Tupilak figures. If I'd had more time there I'm sure there would be more on this list.

The effect that the Pitt Rivers has is profound. The subtle differences from other museums create a warm, cosy, intimate and personal space which is absolutely packed with character. Idiosyncrasies are embraced and celebrated- so what if the displays are packed so full you can't see all the exhibits? Come on one of the night visits and go around the whole place in torchlight and enjoy the feeling of discovery. The place is a riotous excess of pluralism and the 'other worldly' quality it has is giddying. The museum is montage rather than maths, feeling rather than fact and by placing so many different types of exhibit from so broad a reach into such a small space and into such close proximity it allows for wonderful random encounters and associations. At the heart of the Pitt Rivers though is a humanness which pervades throughout. A case full of oil lamps or travel charms shows how different people at different times came up with very different solutions to the same problem, it is this glorious juxtaposition of difference and sameness which the Pitt Rivers basks in.